LIBREVILLE — Behind the tall white walls of a grandiose home belonging to the world’s longest-ruling president, ostriches, buffalo and camels roam neatly landscaped lawns — part of a vast private complex said to include a crocodile wetland and lake topped with lotus flowers.

In the poverty-stricken shell of a city outside, where the poorest pick through garbage for scraps to eat, Omar Bongo’s mustachioed face is omnipresent: gazing solemnly from glass building facades, beaming proudly from ubiquitous billboards, woven into the fabric of countless shirts worn from the coast to the farthest reaches of the forested interior.

He may be short in stature, but he is larger than life in the oil-rich Central African nation he has ruled for 40 years — so long that he’s the only president most of his subdued 1.5 million people (life expectancy, 53) have ever known.

Bongo became the longest-ruling head of state, not counting the monarchs of Britain and Thailand, after Fidel Castro resigned last month, ending 49 years in power.

While most Gabonese genuinely fear the 72-year-old autocrat and there is little opposition, many accept his rule because he has kept his country remarkably peaceful and governed without the sustained brutality characteristic of many dictators.

« God brought him to us and only God can call him away, » said forestry worker Ignasse Minaga, who was born the same year Bongo became president, in 1967. « For us there is only Bongo. He is irreplaceable. »

Minaga lives in the president’s native Bongoville, a tiny village rising out of jungle greenery at the end of a freshly paved road complete with high-wattage, functioning light-poles — luxuries rare in most of Gabon’s undeveloped interior.

Struggling to stabilize after becoming independent of colonial rule in the 1960s, Africa has suffered its share of « Big Men, » many of whom use fear, patronage and rigged elections to cling to power. A few are still around, such as Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi (38 years) and Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang and Angola’s Jose Eduardo dos Santos (28 years).

Like many of the continent’s « Big Men, » Bongo has displayed plenty of dictatorial tendencies. His government has jailed journalists who dared criticize him personally, and has cowed most of the rest into self-censorship. But Gabon’s prisons are not filled with political prisoners and rivals don’t disappear or turn up mysteriously dead in the night.

Instead, he « attacks his opponents by bringing them into his fold, offering them top posts, giving them a piece of the pie, » said Moussirou Mouyama, a linguistics professor at Libreville’s Omar Bongo University. « He’s like a boa constrictor. He suffocates his prey until it’s weak, then swallows it. »

Bongo’s principal opponent in the 2005 election was Pierre Momboundou. After losing the vote by a landslide, Momboundou asked for and got $7 million a year later for development in his constituency (he’s now a member of parliament). He insists the transaction has not defanged his criticism of Bongo. But Gabonese journalists say he doesn’t speak out much anymore.

« It’s belly politics, » Mouyama said. « If you don’t go along, you don’t eat. »

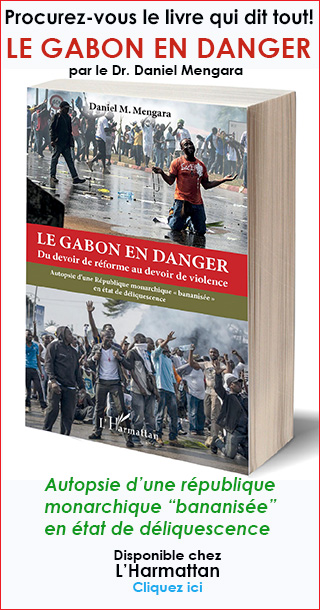

The most vocal critics today are from a movement called « Bongo Must Go, » whose 40-year-old U.S.-based leader Daniel Mengara has called for an armed rebellion (there’s no sign of one).

Gabon today is « neither dictatorship nor democracy, neither paradise nor hell, » said Louis-Gaston Mayila, who heads a pro-Bongo political party from an office featuring a framed photo of him whispering in the president’s ear. « We are something in between. »

That « in-between » has put Gabon in first place among countries in mainland sub-Saharan Africa on the U.N. Human Development Index, which measures literacy, education and other markers of national well-being. It puts Gabon ahead of Africa’s richest economy, South Africa, and its most respected democracy, Botswana.

But Gabon’s wealth depends on dwindling oil reserves, and its democracy is problematic.

Bongo took 26 years to introduce multiparty elections, and polls since then have been marred by allegations of rigging and some unrest. In 2003, parliament — dominated by his supporters — removed presidential term limits from the constitution.

Gabon is the fifth biggest oil exporter in sub-Saharan Africa, and Bongo has built a vast system of patronage, doling out largesse in part through salaries and benefits that come with Cabinet posts. Unlike other Central African countries, Gabon has always managed to pay its civil servants, and has created every young Gabonese’s dream — to be a bureaucrat in a suit, walking air-conditioned halls insulated from the heat and poverty outside.

Bongo has also ensured the strategy covers the country’s four main ethnic groups, which sets Gabon apart from strife-torn Congo or Kenya.

But oil dependency means the country has more oil pipeline (886 miles) than paved roads (582 miles). Only 1 percent of its land is cultivated and Gabon produces virtually no food. Instead, basics such as tomatoes are imported from France, the former colonial master, and neighboring Cameroon, pushing prices so high that Libreville, the capital, is the world’s eighth most expensive city, according to Employment Conditions Abroad International.

Mayila, the pro-Bongo politician, acknowledged « Gabon has its problems. There are no roads, not enough schools, too much unemployment. But we have to fix things on our own time, in our own way — peacefully — not through war. »

« At least I can go to sleep without fearing for my life, » he said. « In this part of Africa, there’s something to be said for that. »

Bongo is regarded by some Gabonese as « the devil they know. » While many would like to see change, they’re also afraid things could get a lot worse if he goes.

« There could be a catastrophic struggle for power — everybody fears that, » said journalist Guy-Christian Mavioga, who was detained for a month in 2007 after publishing an editorial titled « The Last Days of Bongo » and now claims he’d back Bongo to the end.

Gabon once boasted world’s highest champagne consumption per capita, but with oil reserves due to run dry by 2030 and production down by 30 percent in the last decade to 250,000 barrels per day, the party is largely over. Meanwhile, about 90 percent of the country’s income goes to the richest 20 percent the population, while the bottom 30 percent lives on less than $1 a day.

At Libreville’s main garbage dump, half a dozen scavengers assaulted a pile of fresh trash. A man in a torn black beret plucked a tub of curdled apricot yogurt from the rubbish and gulped it down. A 34-year-old father found a broken clock he hoped to sell — to help put his daughter through primary school.

Bongo, by contrast, has amassed a fortune that makes him one of the world’s richest men, according to Freedom House, a private Washington-based democracy watchdog organization. Nobody really knows how much he is worth, but there have been clues.

French media have reported his family owns abundant real estate in France — at one time more Paris properties than any other foreign leader. In 2003, an official of French oil giant Elf Aquitaine testified he had opened several Swiss bank accounts for Bongo into which commissions were paid on multimillion-dollar oil deals. Bongo has vigorously denied receiving any money through the accounts.

Bongo’s daughter-in-law, married to his son the defense minister, appeared on the American reality show « Really Rich Real Estate » in 2006, shopping for a $25 million Beverly Hills mansion.

Though Bongo is married to the daughter of the president of neighboring Republic of Congo, scandals have emerged. In the early 1990s, an Italian fashion designer testified he had flown call girls to the president along with his suits. And in 2004, a visiting Peruvian beauty queen invited to the presidential palace was joined by Bongo, who she said pressed a button to open sliding doors revealing a large bed. She fled in tears, but said Bongo did not touch her.

Born Albert Bernard Bongo, the youngest of 12 children on Dec. 30, 1935, Bongo served as a lieutenant in the French Air Force, then climbed quickly through the civil service and assumed the presidency on Dec. 2, 1967, after Gabon’s first post-independence leader died. Six years later he converted to Islam and took the name Omar.

Today his presidential security staff numbers 1,500, according to the U.S. State Department, while the entire military numbers just 10,000 troops.

Bongo has sought international approval and in May 2004 he visited President Bush at the White House. He has tried to cast himself as a mediator, working to end conflicts in Chad and Central African Republic, where his country has a small contingent of peacekeepers.

That Bongo is likely to remain in power for the foreseeable future seems to be accepted by a population that regards him as the ultimate village chief.

« Gabonese culture dictates that you respect your elders. You can’t say ‘no’ to somebody older than you, » said Moyama, the professor.

Bongo is older than most, « so most people just suffer in silence, » he said. « The problem is, Gabonese don’t dream anymore, and when you don’t dream, your country is in trouble. »